Back in the grunge era, I was fresh out of graduate school, bristling with all kinds of technical knowledge gathered from doctoral coursework in econometrics, multivariate statistics and marketing models and itching to apply it all in my first job as a marketing science analyst. Instead, I spent the first few weeks in training sessions that seemed to involve every aspect of the business except (it seemed to me) analytics. Along with me were new hires from every department – data processing, research management, account management and, marketing sciences. All of us started the training thinking it was a colossal waste of time. Few felt the same way at the end of it.

Back in the grunge era, I was fresh out of graduate school, bristling with all kinds of technical knowledge gathered from doctoral coursework in econometrics, multivariate statistics and marketing models and itching to apply it all in my first job as a marketing science analyst. Instead, I spent the first few weeks in training sessions that seemed to involve every aspect of the business except (it seemed to me) analytics. Along with me were new hires from every department – data processing, research management, account management and, marketing sciences. All of us started the training thinking it was a colossal waste of time. Few felt the same way at the end of it.

We came to understand that the company was not in the business of simply selling “data” to its clients. It provided strategic guidance based on sophisticated market research that was designed and conducted by experts in questionnaire design, survey sampling, consumer behavior, marketing and of course, data collection and statistical modeling. The company could fulfill this mission well only if everyone in the organization had a comprehensive overview of the research process from research design all the way to analysis and final reporting.

The point of this little story is an obvious one – market research is a specialized discipline with a lot of sub-specialties, and it takes training, experience and coordination to achieve excellence. So why make it at all? Sadly, the reason is that like many other industries, market research has become increasingly commoditized. The reasons are many: the advent of technology-driven DIY platforms, procurement, cost pressures, off-shoring, corporate MR departments that are under-staffed and over-worked and so on. I am not going to dwell on any of that. While those things are all true, it is up to us to make the case that there are real differences in market research expertise and that there are tangible things that separate the mediocre from the exceptional. I want to make the case that market research is first and foremost a consulting enterprise. I hope to do that by describing a few things that experienced market research consultants bring to the table; specific traits that make the difference between research that is insightful and useful versus research that is not.

A bird’s eye-view

An experienced qualitative researcher once told me that at the start of a complex multi-country project, she had a clear mental image of the overall project as well as every step in the process. She could therefore foresee potential problems and take steps to avoid them well in advance. This combination of strategic and tactical awareness is the hallmark of an exceptional researcher. The bird’s eye-view is not just about process but also about research design. The more complex the study objectives, the more moving parts there are in the design. The ability to translate the business and market research objectives into an elegant (and streamlined) research design where all the moving parts work in harmony is the hallmark of a great consultant. Mistakes in market research (especially with physicians) are expensive. Knowing how the details fit into the big picture are an invaluable asset in keeping things on track.

Takeaway: Expertise and experience may appear pricey but often end up being cheaper in the long run.

A well-stocked toolkit

A conjoint is not just a conjoint (and sometimes it may not be a conjoint at all). My evolution from marketing science analyst to consultant began when I started to understand the language and the needs of my clients. I remember when I first started, I knew statistical methods, but I had no idea how any of that related to what the clients were saying – it was like they were speaking a different language. Over time (and with the help of outstanding mentors) I began to see how marketing objectives were translated into market research objectives and how research was designed to meet those objectives. This custom aspect is as true for the statistical method as for any other part of the research design. For example, when it comes to conjoint/choice modeling, the specifics of the design depend on:

- Whether it is a product development exercise or a demand assessment

- Whether the product is the company’s first foray in the market or a line extension

- Whether we wish to model competitive response

- Whether we want to model a future market with new competitors

- Whether demand is influenced by the decisions of multiple stakeholders, say physicians, patients and payors

There are endless variations on these objectives. Budgetary and/or sample limitations add an extra layer of complexity and again, there is no substitute for expertise and experience and a robust toolkit. As a consultant, my response to someone who says that “the client wants to do a conjoint” is to gently nudge them towards a discussion of the market the client is competing in, the specific business objectives and the size of sample that was viable. Depending on these factors, the optimal solution may be a full-profile choice model or a partial-profile model or a pair-wise model or some other hybrid approach. Or, maybe what the client really meant was that she wants to assess interest for a fixed product profile – which does not require a model at all!

Takeaway: A well-stocked toolkit and the ability to link those tools to the client’s key objectives and budget result in optimal research designs and maximum bang-for-the-research-dollar.

The ability to improvise

Most of the elements of the marketing scientist’s toolkit come from the sterile environs of academia. The ability to take these tools and apply them in the messy world of market research requires an intrinsic talent for improvisation. We are frequently called upon to address issues that are simply not interesting (or visible) to the academic researcher. This requires that we take these tools and extend them in ways that are not obvious and might possibly be frowned upon by academics. However, these improvisations are essential in applying these tools in ways that are useful to our clients.

Some years ago, I was working on a demand assessment in which we were testing multiple entrants in a new class of treatments for a chronic disease. The research design involved a discrete choice exercise in which we presented multiple products with varying profiles and a “none of these” option. The data from the choice model was further linked to a few allocation exercises that included the new as well as existing treatments. We could then assess demand (i.e. share of patients) for all the new products given varying levels of performance in a competitive context. The wrinkle, however, was this: the mathematics of the multinomial logit model compels each new product to receive a non-zero share, drawn from the existing treatments. This result was unrealistic because the model would predict that these five new treatments would gain more than 50% of the market – all these products had the same mechanism of action and were collectively unlikely to gain that much share. The team felt the more realistic scenario was that there was an upper bound to the share gathered by the class and that limit was likely set by the product with the best perceived performance. Applying this conceptual idea into the simulator required some…improvisation! We expressed the choice probabilities both in binomial and multinomial terms. The binomial choice probabilities represented the share each product would get if it was the only new entrant. The binomial patient share for the best performing product was used as the limit that could be achieved by the class and then the multinomial logit probabilities were used to calculate the relative shares of the new treatments based on the limit. So, for example, if the best performing product was to get 30% based on the binomial probabilities, the 5 treatments would split the 30% based on the multinomial probabilities. This ensured that they collectively did not achieve an unrealistic share simply based on the mathematics of the model. Further, the relative shares accurately reflected the preferences implied by the estimated utility functions. This approach may not necessarily work in another context, but the point is that experienced researchers are always able to extend existing methodologies to meet the needs of the moment.

Takeaway: If market research is to serve its purpose of informing business decisions, its tools must be used in an improvisational and creative way to meet the needs of each project.

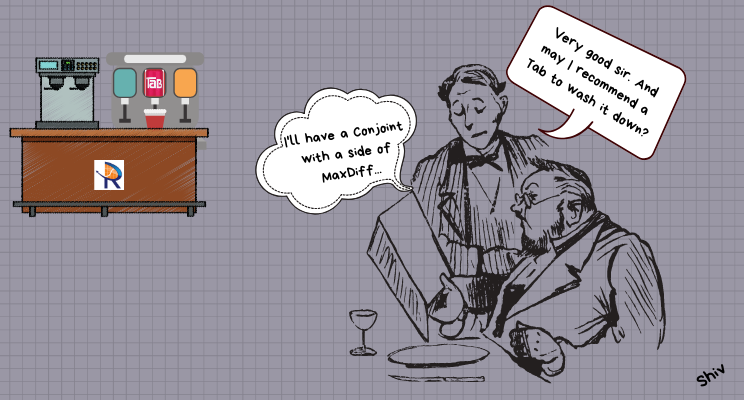

If there is a common thread running through this essay, it is that market research consulting is no different from any other form of consulting – it is based on subject-matter expertise and involves listening carefully to the clients’ objectives and gaining a high-level perspective before drilling into the details. Much as they happen to be my bread and butter, statistical methodologies are simply the details of how we get to the desired outcome – as consultants, we cannot start there. Every time we “take an order” for a MaxDiff or a Conjoint without engaging in a broader discussion of business objectives, we relinquish our role as consultants. This simply perpetuates the idea that market research is a commodity. The more seriously we take our jobs as consultants, the more likely it is that the marketplace will view us as such. And flies will have to go bother someone else.